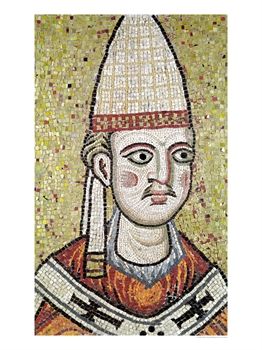

Languedoc in the 12th century witnessed the rise of one of the most remarkable heretical movements in the Middle Ages. These believers we have come to call the Cathars, but they probably began as little more than a lose band of believers who argued the finer points of their faith with each other. Eventually, they would come into mortal conflict over the broader points of the world with the Roman Catholic Church.

For its part, the Church would use any number of methods of coercion against these heretics while Cathar “good men” and “good women” refused to partake in any violence at all, including against terrestrial animals and creatures as meek as a squirrel. So while the Cathars would make their case through the Christian qualities of humility, peace and compassion, the Catholic Church would resort to the ace up its medieval sleeve – brute force.

The Church had to innovate. The Dominicans, or the Order of Preachers, would be established and trained to debate the finer points of “Christian Love” with these and other heretics in the medieval town squares throughout the Languedoc. Their efforts were a massive failure, but eventually, these monks, along with the Franciscans, would man and administer the Papal Inquisition and bring heretical offenders to the gaols and pyres of the state.

Like Manichaeans, the Cathar faithful were divided into believers or “credenti” and the “perfecti” or those who taught. Cathar faith dictated that the perfecti must always tell the truth and they would die before renouncing their faith. They died. They died in the brutal crusade designed to destroy their beliefs. They died in the dungeons and on the pyres across the Occitan.

Some argue whether Cathars or even other “heresies”, gnostic or other, could indeed be properly labeled as part of the Christian faith. This argument generally comes from the vantage of established Christian orthodoxy and does not necessarily entail a real debate about the true message of Christ.

Still, there were similarities between Catharism and orthodox Christianity, for example:

- Celibacy – By the Eleventh Century’s Gregorian Reform, clerical celibacy was strengthened in the Church. This was something that Cathar perfecti were supposed to practice as well.

- Poverty – Monastic vows of poverty actually became more in vogue with the rise of Cathar, Waldensian and other heresies. Indeed, St. Francis and his order of mendicant Friars Minor can be seen as part of the same drive for the apostolic life that compelled heterodoxy throughout the High Middle Ages. While the Church itself, and much of the lay clergy, were anything but impoverished, Cathars seem to have forsaken much of the trappings and the wealth of the Church.

- The Divine Humanity of Christ – The Church’s view expressed after the First Council of Nicaea was that Christ was both human and divine or He “was incarnate and was made man”. The nature of the savior was of paramount importance for this council established to decide right belief (orthodoxy) from error (or heresy). With Cathars, there were likely different beliefs – certainly many radical Gnostics maintained Christ was not human, but purely divine. It may be that the prevalent belief among Cathars was that all humans had the spark of divinity and were what was called Aeons or “angels”. One might even go so far as to argue that Gnosticism’s “secret knowledge” was this very divinity of humankind.

Of course, the differences were striking enough to compel the Church to eventually act:

- Ecclesiastical structure – The Cathars likely didn’t have much organization until some semblance of this was deemed necessary for survival after the Treaty of Meaux in 1229.

- Dualism – Catharism, like Manichaeism, was a dualistic belief that held that the material realm was evil while the spiritual realm was good. Radical dualism went further and held that Satan was a co-equal in power to God. While some believe that Catharism may have moved towards radical dualism in the early 13th century it is almost certain that the Church lumped all dualistic heretics into a single category. The truth may have been that the dualism Cathars debated within their “faith” was more complex than simply the “belief in two gods”.

- Oaths – Feudal Europe itself was built on the foundation of oath-giving and the Church provided needed sacred legitimacy along with the symbols, icons and relics upon which many vows were sealed. We see a great deal of this even today, yet Cathars, and indeed many heretics through the ages, wholly rejected any oath-taking as sinful and wrong. Indeed, this became a way of identifying heretics from among the flock of the Church’s faithful.

- Vegetarianism and Pacifism – Cathar perfecti were virtual vegans not eating any animal products with the possible exception of fish. Many early Christians, such as the Ebionites, shared this quality along with eastern religious traditions such as Hinduism and Buddhism. Early Christians were staunchly non-violent and it seems Cathars were as well. This general pacifism likely included many of the credenti although by the time of the Albigensian Crusade (originally preached by Pope Innocent III), many Cathar believers certainly took up arms to defend themselves, their families and property. A popular test of heresy throughout the European Middle Ages was “the chicken test” where a suspect was required to kill a chicken as proof of the orthodoxy of their beliefs.

- Sex and the Sexes – While the Church barred women from the clergy (and continues to do so), it is apparent that there were no such restrictions for Cathar perfecti. For the believers, or credenti, sexual mores seemed more liberated than with the Church. Sex within marriage may have even been considered less desirable than sex outside of marriage for many Cathars since one would not necessarily recognize their own moral faults within the (Church’s) sacrament of marriage. It is also true that sex within marriage led to procreation and it was a Gnostic tenet that procreation perpetuated the evil material realm. It has been argued that for Cathars even sodomy and homosexuality was preferable over marriage. Of course, the Church took this to their usual level of hysteria in denouncing their enemies. Cathars were accused of all sorts of sodomy and sexual misconduct. Our word “Bugger” has its roots in this hatred for the “Bogomils” or “Bulgarians” who traveled about in pairs.

- Relics and Icons – The medieval Church believed holy relics – the bones, blood, clothing or other paraphernalia of saints’ and martyrs’ remains – held special powers. The significance of this power is very hard for modern readers to grasp, but it was critical to the Church and to its power through the Middle Ages. Cathars and many other medieval heretics went so far as to abhor the cross as the instrument of Christ’s murder. These heretics saw the symbolism of the Church as idolatry and disdained the rich trappings, the ceremony and the ritual of a corrupt Church.

- The Resurrection of the Flesh – This belief, still held by the Church, maintained that at the end of time, the dead would literally rise from their graves in their earthly bodies. Somehow, this is made to work within the cosmology of an otherworldly Heaven and Hell that the Church made as central to their cosmology. Cathars held beliefs shared among many Gnostics – the Manichaeans and the Bogomils – as well as Hindus and Buddhists. They believed that the souls of the departed reincarnated and were born again in this world. For Cathars, it is more likely that in the end times all the Aeons would return in preparation for a sort of universal redemption. Compared with the orthodoxy of the Church, “the Great Heresy” naturally seemed much more tolerant. It has been argued that the most striking difference of all between heresy and orthodoxy was the oppressive machinations of an oppressive Catholic Church made up of edicts of negative rules that so starkly contrasted with the Gnostic positive morality that encouraged perseverance in the quest for purity.

- Transubstantiation – This was another contested belief ridiculed by the Cathar faithful. According to the Church, during the ceremony of the mass, the Eucharist bread and wine would literally (that’s literally) and somewhat magically transform into the literal body and blood of Jesus Christ. A running Cathar joke in the Languedoc pondered the size of the mountains of holy excrement that would result.

Scholars today understand more about the first Christianities, their diversity and they have discovered relationships with Catharism and early Christianity that seems to be absent with the later orthodoxy. In Edward Gibbon we hear descriptions of early Christians as, “offended by the use of oaths, by pomp of magistracy, and by the active contention of public life”. He goes on that early Christians held it unlawful to ever “shed blood of our fellow-creatures”.

By the Twelfth Century, a morally bankrupt Church faced a growing population of believers who thirsted for the apostolic life. The Church responded effectively enough to stave off widespread dissent for another 300 years. Simply put, through “any means necessary”, the heretics had to disappear. They represented a serious threat to the spiritual hegemony of the Catholic Church who controlled the populace through their ordained position as intermediaries between mankind and God.

The longest crusade in history was fought to erase them from the Languedoc and when this didn’t do the trick the Church perfected the machinations of the indomitable Inquisition. The majority of a recalcitrant perfecti ended up finding their end on the stake, but it would take the Church another 100 years to complete their genocide.

Was it God’s Holy Church that was anointed to persecute and eradicate the “good men and women” of the Languedoc or were the Cathars the real martyrs of an oppressive and corrupt institution at the height of its unholy evil?

Further Reading

Barber, Malcolm. The Cathars.

Gibbon, Edward. The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

Le Roy Ladurie, Emmanuel. Montaillou (highly recommended).

Markale, Jean. Montségur and the Mystery of the Cathars.

Moore, R.I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society (highly recommended).

Weis, René. The Yellow Cross.

This post originally appeared in the Reveille website on January 9, 2017 and is republished here with only minor modifications.